Dialogue on Fearcriminalysis (Part 1): R. Michael Fisher, B. Maria Kumar and Desh Subba

I am intrigued by the long standing traditional ethic in law, be it judges or police officers that they are to do their duty “without fear or prejudice.” Easier said than done. -R. Michael Fisher

Editorial Preamble:

I (R. Michael Fisher) took on the initiative to start this sub-field of Fearcriminalysis because of the recent email communications of Desh Subba (founder of philosophy of fearism) with B. Maria Kumar. See our bios at the end of this dialogue. I thank both of my colleagues for their important work and life experiences and how they have so easily and sincerely taken-on this dialogue series I envision on Fearcriminalysis, as we explore together the first roots of what this sub-field may entail.

Recently, I wrote on a FMning blog “What I have learned over my 45 years of teaching, more or less, professionally, with then getting three post-secondary degrees in Education as a field, is that it is good to continually reflect not only on our thinking and content, but on how we design curricula, how we imagine the nature of the human being, and how we actually teach in diverse conditions and to whom.” The analogy with “teaching” (and learning) that I was speaking about seems very appropriate when it comes to the field of governance, law, criminology, etc., of which Fearcriminalysis is focused on. I am intrigued by the long standing traditional ethic in law, be it judges or police officers that they are to do their duty “without fear or prejudice.” Easier said than done.

Like Subba and Kumar, I am interested in how we design organizations and governance, create laws (facilitate authority- power structures), make rules, regulations, policies and practices of enforcing them. Our imaginary in designing for such work are often passed on from past generations, protocols, institutional traditions, cultural and religious habits and often without a lot of critical thinking and examination of the deeper (and invisible) assumptions behind such ‘norms,’ ‘beliefs’ and practices of governance and law. And, concomitantly, our assumptions behind those who ‘break’ the law. Thus, our focus of conversation involves the political but focuses on criminological aspects in the largest sense where fear is important to account for.

Regarding tradition, although we each respect it in its best offerings, just because something was and is done this way or that, certainly doesn’t mean by necessity it is the “best” way. We all love inquiry and change. But then we have to define what best and better are, and in what context are such qualitative and/or quantitative assessments made. I’ll never forget the trial of the late Mahatma Gandhi in the British courts of India during colonization, where he more or less said to the judge and jury, “You may be following your laws, but I am following justice.” And, on that difference, Gandhi was charged and imprisoned, a similar story to the late Nelson Mandala in S. Africa.

There are always hidden biases, for nothing is value-neutral when it comes to how to best organize and manage societies. I am interested in the issue of fear-based laws, rules, etc., and what would fearlessness-based laws, rules, etc. look like in contrast and would they work better? I would like to address in this series of dialogues the notion of a Fearlessness Paradigm for law. Tagore seemed to point to the possibility of a new society, after my own heart, when he wrote, ”where the mind is without fear....into that heaven of freedom, my Father! let my country awake.” [thanks Maria, for sharing this relevant quote]

It is evident in the dialogue below the three of us quickly move into discussions of human nature, the human condition and the human potential, at least implicitly. Our own “politics” may also come through somewhat in these discussions. There is every intent in the dialogue to be non-dogmatic, non-coercive and at least listen to each others’ views respectfully, even if at times we may not all agree. The articulating worldviews, philosophies, values and methodologies that come from how we see relationships in society are important to analyze as well as the pragmatic details of governance, for e.g., policing and security, of which Kumar especially has a long track-record of highly accomplished professional competency that he brings to the table of the discussion on the nature and role of fear related to governance in India. It is also obvious that the disciplines we draw on in the discussion, although mostly about governance and law, one can see we dip into anthropology, sociology, social psychology and criminal psychology, flowing back and forth as the conversation develops. As Editor of this dialogue it was challenging also at times to interpret our words, our linguistic meanings by email, as we come from different cultures and parts of the world, with various degrees of background in English language use and writing. Each of us can Comment on this dialogue on the FMning as well to enhance and/or clarify points made.

Clearly, the world is in a lot of crises these days. Political tensions and nuclear war has never been so high a probability since many decades. The global Fear Problem is self-evident. How countries, cities, and people in general get along and/or don’t get along is crucial to the outcomes of how we are best going to solve ecological, social and political problems. Conflict is inevitable in such diverse landscapes and mindscapes of differing cultural backgrounds, and even “Culture Wars,” and so Fearcriminalysis seems ready to emerge to help out. I tend to agree with the contemplative Thomas Merton that “At the root of all war is fear” not unlike Subba’s (2014) claim, “War, murder, terror, etc. are produced by fear. Anger, conspiracy, suspicion, and hatred are produced by the fear…” (p. 11). That is, fear which is not understood or managed very well. From my research, no full attention has been given to “fear” systematically in relation to governance and law, even though fear is mentioned and seen as a factor (e.g., “fear of crime,” or “freedom from fear” in the UN Declaration of Human Rights). Centralizing analysis, through what Subba (2014) called a “fearist perspective” (lens), as the philosophy of fearism and fearology suggest, can be very valuable. This is totally new and exciting exploratory territory.

I personally, cannot think of a more important topic than these critical issues of governance and what democracies may look like that better serve the people (of all kinds). I also cannot think of a more controversial topic. In my experience in the past, be it with government leaders, bureaucrats, police, or military, or teachers and/or parents and citizens-- everyone has very strong opinions on the “best” ways to govern and keep law and social and moral order. But we need more than “opinions” to rule a society and be healthy, sane and sustainable in all ways that are moral and just. Governance and its institutionalization, on the macro-scale, is much like being parents raising children at home, or schooling them—there are a lot of “hot” contentious views in this domain. We are talking about Authority and Power every moment we talk about governance and law(s). And at the same time, we are talking about Fear related to Authority and Power and issues of freedom or non-freedom. Big stuff. So, without further comment, let’s proceed and let you the reader experience and interpret what is going on in the dialogue(s) and how we may shape Fearcriminalysis. We hope you will Comment on this blog, and/or send us personal emails as well (see bio.’s and contact info. at the end of this Dialogue).

The Dialogue:

[Ed.: For readers of this dialogue, and to remind each of us (Subba, Kumar and Fisher), I have copied [1] my recent correspondence with you both re: Fearcriminalysis (the name I coined), just to get us started, and after that it is anything goes, as an emergent creative exchange.]

Fisher: In regard to your background Maria, which I know little about re: policing and your writing and publishing, I did want to share with you that I have thought for some time that the Fearlessness Movement or whatever we call it has to bring a new radical paradigm to inform new research, thinking and applications re: fearology, fearanalysis, and feariatry, also terms Desh has used to all sorts of domains of society today.

What has not been talked so much about in Subba’s and my work is that we need to bring the study of fear and fearism in closer relations to the entire world of law, criminology, safety and security, i.e., social order--so, that we can take new and better directions in the future of governance and in how we manage societies and the plagues of phenomena like the growing "fear of crime," “fear of policing,” "terrorism." etc. There's a larger conversation I'd be glad to engage with you and Subba, if you are interested in being part of another sub-discipline of philosophy of fearism that directly relates to the above, perhaps we call it Fearcriminalysis? This would be the next specialty study for the 21st century, so that we truly can begin to turn around the growing toxic "culture of fear" that is invading all aspects of life for virtually everyone.

"I watch people running towards the objective of happiness be that achieved individually or in groups. Unfortunately, this aim is undermined somewhat by the ‘Free World,’ which is changing to more value on competitive aims and financial gain." - Desh Subba

Kumar: I appreciate your kind gesture in sending information about your brain child, i.e., Fearlessness Movement and references to your books, blog, tech papers etc. Desh and I are also recently corresponding and exchanging books. It will take some time to study this material to familiarise myself with both your research and teaching projects, which are quite important.

As regards to your observations on prospective expansion of fearism into the realm of crime, law, public safety and order, etc. I would like to say that it is a brilliant idea to pursue and if you and Desh Subba could guide me, I will certainly put in my efforts to work on Fearcriminalysis with you both. Having been in India’s police service as a career for the last 32 years, I have had first hand experiences about how people fear not only crime and criminals but also policing and police and other crime fighters; which is itself intriguingly a paradoxical reality.

Fisher: This is wonderful news Maria to be able to develop the sub-fields of fearism having a practitioner like yourself working alongside the philosophizing and theorizing that Desh and I have done. I note from your recent correspondence you also appear to love writing, poetry and you quote famous philosophers and mystics. That was sweet music to my ears.

We’d equally like to find a psychiatrist to work with to develop Feariatry. So, I’m curious how Desh you respond to Maria coming to this work on Fearcriminalysis at this time and what you see happening in this area of law, safety and security, etc.? I know for an example, you have a professional side career, beyond being a philosopher, writer and poet—you are a security guard in Hong Kong.

Subba: I am honored Maria has been offering to help us out. He has a prestigious reputation. Yes, I am. Somewhat like policing, our job is to provide a sense of security through watch and secure. I have since being a child closely watched the activities of people. Aristotle once mentioned that the aim of humans ought to be happiness. And happiness is not only an emotion, it involves activities. Those activities must be unique. I watch people running towards the objective of happiness be that achieved individually or in groups. Unfortunately, this aim is undermined somewhat by the ‘Free World,’ which is changing to more value on competitive aims and financial gain. I observe this kind of world creates more fear for them and less happiness the harder they strive. Between being human and finding happiness they need to cross many barriers. Every barrier is full of fear. It is not easy to reach the top of happiness.

Fisher: It has long struck me as I observe people in competitive modern societies that they seem not to be conscious of the contradiction between the high value put on competitiveness, usually a win-lose scenario and how it undermines human happiness because the latter is undermined by feeling more insecure, i.e., fearful. In a sense, it is logical that “feeling safe” is not going to be secured under highly competitive societal structures and processes of winners and losers. After my own education in such a North American society and being a school teacher and curriculum designer and social critic, it is more than obvious children generally are not very happy in these systems—mostly, they are very frightened and motivated by fear nearly chronically, and I think in postmodern society this has got worse. Insecurity is the dis-ease of choice, so it seems ironically in a society constantly seeking “safety and security” in order to avoid risk; a paradox many sociologists have seen, e.g., in labeling the West’s “risk society” [2].

Subba: I used to watch activities of the rich man to the poor man. Most of rich couldn't sleep at night. They wake up and drive their car early in the morning, even at 2am, 3 am., Because they are burning inside and try to cool it. Sometimes they used to take lot of medicine. I am first witness of their hide and seek activities. They used to leave medicine and 4 or 5 mobiles in guard room. These mobiles used to call entertainment girls. They keep all these in the guard room and keep away from the reach of their wives. Sometimes I watch office staff. They come early 3 or 4 o’clock to work. Their office time is 9 am. They have been given some task by manager. They must complete assignment work within tight time frames. Otherwise they lose commission, promotion and remuneration. They are always running behind so called “happiness.” It makes them hard, fast and better workers but that is where things fall short.

The rich man fears losses: losing name and fame. To maintain it he suffers from anxiety, stress, fear, depression. Similarly, employee fears losing their job, income and family and social status. It gives overload, burden, restless etc. Slowly these activities change into sickness physically and mentally. Family life is more strained.

For these people, rich and/or poor, to meet their demand, they engage in lying, smuggling, stealing, and blackmailing. Sometimes it changes into family and social violence. These are crimes. The source of the crime maybe differs, but to solve crime we need to follow the surface symptoms of behaviors to the deeper root causes. Directly of indirectly, some parts of fear must be examined there. If we treat the root, some crime can be cured.

Kumar: Let me at the outset congratulate you all on your unfailing enthusiasm and dedicated yeoman service for the cause of fearism. Truly, with Mr. Oshinakachi Akuma Kalu, I believe you have hit the nail on the head when you wrote [Desh’s book subtitle]: ”life is conducted, directed and controlled by the fear.”

As we all know, Rabindranath Tagore, the first Asian to win the Nobel Prize in Literature (1913), became synonymous with his emphatic lines when he wrote, ”where the mind is without fear....into that heaven of freedom, my Father! let my country awake.” Unless fear is undone, freedom has no meaning for existence, rather existence has no meaning. It is here in this existential context of political life, that whether it is the American Declaration of Independence, or any other democratically-based national constitutional provisions and laws, there ought to be fearlessness alongside the inalienable rights of life, liberty, pursuit of happiness, fraternity, justice and equality.

As I see it, knowing about handling or managing of fear well, as a philosophy of fearism promotes, is more potent than the feeling of being safe.

Fisher: Indeed, Kumar that is a powerful statement from someone in policing. I think the recent “safety” and “risk” discourses, especially in the West are excessive, if not neurotic and fear-based themselves. In general, I find, people care more about lowering risk, and striving for safety and security, than being moral citizens. In one philosophy conference I presented in my graduate years, I entitled the talk “Better Safe Than Moral.” This was a horrible state of affairs we had entered as societies. People seeking low risk and safety all the time easily become so dependent on someone, like authoritative “forces” or “law” or “policy” to protect their safety but rarely then do they take responsibility anymore for their own actions, and the very fact that risk is part of life if one wants to be a creative developing and maturing person. Worse, dictatorships more or less begin within this matrix of fearfulness of citizens who cower under all authorities and thus give over to them to rule with the iron fist. I see a lot of this happening in Western so-called “advanced” societies like in Europe and the USA today. Not a good sign of the future.

Kumar: True Dr.Fisher! Most of the people tend to care more about lowering risk than being moral citizens.

Fisher: Maria, is this human behavior even in India where you live and work? Do you think this tendency is part of human nature? Or, is it part of the human condition(ing)? Explain your views.

Kumar: I think that it hardly has anything to with India or any other country but strongly indicates that it is part of human nature in general. In a way, ‘lowering risk’ and ‘striving to be moral’ are equally important in the sense that they are complementary to each other. One alone can not bring in desired good because these two strategies need to be attended to in terms of prioritisation as well as simultaneity. Because, ‘risk management’ (i.e., lowering risk) is a short-term goal, usually because of its urgency. For example, a thirsty deer is about to drink water at a river but on sighting a lion in the vicinity, it immediately sprints away without touching water, in its bid to escape its life from the imminent danger. So is the case with anyone, who feels threatened and tries to minimise or avoid risk. If secure for the time being, then one has to the option to strive to be moralistic and ethical as a long-term goal.

Fisher: Sounds like Maslow’s hierarchy of needs theory explaining developmental and motivational priorities. In this sense, “true fear,” as Gavin de Becker, international security expert, would label it as the “gift of fear” [3] acts just as it is designed by evolution as good Defense Intelligence to reduce immanent and/or potential threat. So far no problem, our instincts as Nature’s gifts are working the system for best outcomes—not necessarily guarantees of safety but a likely best probability of least harm.

Kumar: But caution is warranted while handling a threat and lowering risk in the sense that it should not result in the creation of more or bigger risks, since I am reminded of Friedrich Nietzsche’s warning, “whoever fights monster should see to it that in the process, he should not become a monster.” As Michael is rightly apprehensive, Nietzsche’s apt quote serves as a red alert if the citizens cower under all authority and vest unbridled powers in the dictatorship to rule with an iron fist.

...civilisations also went on regulating the conduct of subjects/citizens through formal laws. Then what happens if regulations, enforcement and controls become more intense? Too much of regulation through laws and rules proves to be more harmful than helpful. If any aspect of human behaviour is controlled by unlimited creation and application of rules in the name of crime prevention, safety or maintenance of peace and order, what will happen to society as a whole? " -B. Maria Kumar

Fisher: Then the social contract and basic trust, the republic and its principles, all take a dive and democracy itself is threatened or collapses. Terror(ism) is released, more or less. The classic is fighting “the enemy” who is “evil” over there as having weapons they could use against us, and so, pre-emptively, let’s strike them with our bigger weapon first. For example, the spiraling nuclear warheads phenomena—that is Fear Wars, fits this, and shows how easily, when perceptions and worries lead to decisions that are chronically fear-based, we end up with bigger risks—e.g., US and N. Korea for one, and maybe the same for India and Pakistan, and many gang wars, etc. War itself seems to fall into this wrong thinking as Nietzsche was getting at. In other words, It’s sort of bad policing all around. I also think your deer and lion example is only partly successful as explanation when we apply prioritisation principles to a chronically worrying sub-set of humans, that is, who are neurotically fear-based people living in culture—living under oppressive conditions [4]. Human nature is now operative, more or less, as the human condition—the latter, a Defense Intelligence undermined and compromised by what de Becker calls “false fear.” Now risk assessment, in a postmodern “risk society,” often is exaggerated to default on the ‘worst scenario’ when there is no real evidence for it. This is the opposite of Tagore’s ideal, because the mind is filled with fear and worry and a big brain that can project that fear into the future (unlike a deer). A more complex explanation and theory is required here. Anyways, Maria could we get back to your views about the haves and the have-nots that Desh spoke about earlier.

Kumar: Let me start with an observation of four categories I have observed and named. I’ll distinguish two generic types of peoples’ patterns distinguished within the haves and have-nots. Some of such people are have-nots whose primary aim is to survive. I call them “literal survivors.” These struggling literal survivors can be of two sub-types. The first sub-type may struggle morally, ethically and lawfully to secure their most basic needs like food/water and sex—that is, the instinctual goals of existence-food for self-survival and sex for familial, tribal and/or survival of the species. Say for example that someone of this sub-type having no means of livelihood shows initiative to take-up manual work as a farmhand and marries a girl as per normal legal procedures. Let us call such people “socially approved literal survivors.”

The second sub-type of have-nots are those who struggle for existence by ‘hook or crook’ without little if any concern for upholding social standards of morals, ethics or laws; say for example that a man is starving and resorts to robbing a passer-by and/or raping a lonely vulnerable girl as instinctual acting-out. We may term them as “socially disapproved literal survivors.”

Fisher: I think this second sub-type nicely fits, for the most part, what criminologists and psychologists would label “deviants,” and Subba might call “corrupt people” [5] of which I tend to prefer to name and theorize generically as “rebels.” The issue of one’s relationship to Authority/Power becomes a major factor in outcomes of these actors and their interactions. A point, perhaps, later we can return in regard to the relationship and role fear plays in these authority-power-control and ‘game’ dynamics in governance and law.

Kumar: Okay, regarding the haves, on the other hand, as the more well-to-do people, I see two sub-types under the generic label “lateral survivors.” They don’t need to struggle for food and sex. They just want to survive their current affluent status (i.e., status quo), meaning that they don’t want to go down below the current standards of living.

Subba: They fear falling and failing. It is fear accompanied often by guilt and shame, if not terror deep down.

Kumar: Yes, it’s this fear that tends to dominate their motivations. They have to keep up the present sophistication and norms. During the course of their efforts to maintain this sameness in status, some people follow morals, ethics, and laws to do so. This sub-type we may refer to as “socially approved lateral survivors.” Similar in motivations, but strategically in contrast to the first, are those who don’t adhere to standard rules, morals and laws, these are the “socially disapproved lateral survivors.”

The socially disapproved literal survivors and the socially disapproved lateral survivors are well aware of the unsavory consequences like penalties, and legal sentences, etc. for their illegal and immoral activities; hence they continually try to lower the risks and uncertainties involved in achieving their objectives. These people feel threatened by the ‘long arm’ of the law and by lawful defenders and are more fearful of Authority.

Fisher: Are you saying the haves/laterals are more fear-based in general than the have-nots/literals? If so, that seems counterintuitive at first glance, doesn’t it? I think Desh might agree with you, as he has argued in his philosophy of fearism that people living more simple lives, e.g., traditional villagers without formal education, without high tech, and living closer to Nature and outside of big cities, etc., are generally less fearful and less fear-driven than modern urban dwellers living more complex and “well-educated” lives.

Kumar: No, I think the opposite; the socially approved survivors, whether literal or lateral, are less fearful; and less fearful in the sense that they are concerned only about natural hazards or sudden change in policy etc.. like a cargo truck washed away by unexpected floods or their share-values fell due to new pricing regulations.

Subba: I have, as Michael says, hypothesized that the better well-off generally are the more fearful compared to the less well-off. In my book Subba (2014), “After the fulfilment of all these stages [in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs], they live their lives happily. But they are more aware of some things than the common people [at less advanced stages]….they have a lot of stress in regard to the[ir] security of property, necessity, and increment of investment. They always have the fear of downfall from the[ir] present position. If they have a little loss in their business, they feel as if they are completely hopeless. That is why they are hard-working; they work day and night at the cost of their health” (p. 288). [6]

Fisher: Desh, in your 2014 book you give attention to this hypothesis in your views on rural simple-traditional lifestyles vs. urban modern life-styles [7], as well you wrote about a model--“Pyramid of Renowned Person” Figure No. 71, and bluntly say, “According to this pyramid, most famous people have the highest fear and ordinary people have the lowest fear. Since ordinary people have the least fear, they have the freedom to walk wherever they want and also they don’t fear to walk wherever they like and eat whatever they like…” (p. 233). I think your security guard experience may have informed this view? Perhaps also your study of Marxism and class? Desh, where did this hypothesis, re: haves and have-nots, start in your thinking? And, I’d like to hear more what Maria thinks of it.

Subba: You know Michael, I have less theoretical basis and bookish knowledge for this view. I mostly do practical study. What I mentioned above can seen by everybody. When people rise in hierarchy needs, more and more, they fear more and keep more bodyguards, keep CCTV, bullet proof cars. Without checking proper security, they never dare to travel, walk freely. It is right, when people have nothing, that person has less enemies, jealousy, kidnapper, torturer, and harm. A coolie, labourer, daily wage worker normally has less fear and fears less heath and diet problems.

Fisher: It’s interesting that, at least in North America, the sociologist Barry Glassner, famous for his book on the “culture of fear” studied also the great worry and fear over what people eat these days because of a sense of always something is going to cause some health problem [8]. They listen to the news way too much and read too much about warning reports and often they have contradictory results. It leaves the informed consumer confused often. I don’t think people on bare survival on the street worry much at all about the same neurotic details of diet and health choices. I don’t suspect they listen to the mainstream media news two or three times a day or read newspapers often as daily diet. Though, in extreme cases they may fear starving to death or freezing at nights. But generally the street comm-unities take care of each other because they are all vulnerable together. In competitive and well-to-do communities people are more isolated, although they do have extra money to insulate themselves from disease and death too. It’s complex to generalize but I do think you have a good point Desh. I don’t know if it has ever been systematically researched. I wonder how it may be something relevant to our topic of law, social order and policing? It is relevant to Kumar’s model of literal survivors and how they are perceived as deviants—maybe, they are less fearful people (more fearless?) and in that sense “healthier” than the richer? Maybe if this is true, we would see them differently when we are in the middle and upper classes? I wonder. Maybe we could learn something from them about fear management?

Kumar: Yes Michael. What I opine is that riches, fame, name, power and status may bring in fear at times as shown in Subba’s model of Pyramid of Renowned Person but it may not be generalized because there are many great people in history who walked around freely. We know that the Danish king used to bicycle alone on the streets. Mahatma Gandhi was always amidst masses but he was not afraid of being killed, though as irony has it, he was shot dead by the assailant at a prayer meeting. Despite being great, one’s security can be compromised, as some people are “too bold” in terms of spiritual strength-- being loving, caring and humble. Mother Teresa of Kolkata was one example. On the other hand, the down-trodden poor like untouchables of ancient Kerala in India fear to come near to a Brahmin, so they maintain a distance of 10-20 steps or so, lest the upper castes become impure. And the untouchables may even incur legal penalties.

Fisher: This kind of code of law is based mostly around mythological-based fears that have infiltrated the culture, even if somewhat irrational, even if they may have once had meaning in earlier times--or even if they are unjustice we might say, there’s real pressures and fears as you say, regardless of reason and rationality and life in a modern world. I suppose such primal magical and mythical fears are “laws” (or taboos) that have their own logic developmentally and they can be recalcitrant to change and adaptation over time. Fear (i.e., taboos) are powerful shapers of social life and law(s). They are also the basis of a good deal of prejudice unfortunately, and they spread a culture of fear as well, even in non-industrialized countries. No small problem, from an ethical and fearist’s perspective. It is difficult for me as a modern Westerner to get my head around how an untouchable caste put upon a person is treated like this via criminalization for such an ‘innocent’ event like walking to close to another person (i.e., the upper-caste) in public space—where is freedom in that? I think Mahatma Gandhi, espousing a philosophy of fearlessness and liberation for all, was on a mission to change these traditional ways. No wonder he was assassinated, for he was not only challenging the British Rule but also India’s Religious Traditional Rule—which, I would guess he saw both as unnecessarily fear-inducing—and, ultimately creating unnecessary fragmenting and polarizing against the establishing of a just sense of modern liberty, governance, law, security and social/moral order—that is, of a true (ethical and spiritual) community and democracy.

Kumar: Indeed. This ‘forced fear’ seems to have been ingrained and conditioned in the minds of lower castes in such a manner that it led Dr. B.R. Ambedkar, the architect of the Constitution of modern India to say: ”so long as you do not achieve social liberty, whatever freedom provided by the law, is of no avail to you.” I also suppose that it may perhaps depend upon the person’s state of mind as to feel fearsome or fearful, depending upon various factors. Relevant here is Steve Biko’s eye-opener observation, “the most potent weapon in the hands of oppressor is the mind of the oppressed.”

Subba: I discussed in my Philosophy of Fearism (2014) book the “Fear Weapon” of which is the worst configuration of fear in history (pp. 235-38). I write about law and criminals and how people fear to violate rules and laws. They fear going to prison. This is essential to society, but it can be abused. However, we have to recognize what fearism reveals over history, and that is that fear is one of the most powerful weapons to use to maintain law and order from tribes to grand nations and even over the world. It makes people more disciplined so they can function in groups and that’s a good thing generally.

Kumar: As also pointed out by Subba earlier in this dialogue, well-to-do people do nurse fear about their wealth that it might be taken away or about how it could be secured/preserved. Same way, poor people also suffer due to fear of uncertainty about how the future holds for them in terms of socioeconomic well-being. It was also clearly visible in ancient India that the people of lower castes were more fearful than upper castes because of societal sanction accorded in the texts of some scriptures. In the 19th century of Europe also, Karl Marx felt that the upper classes were more powerful whereas the lower classes were more fearful. It is in this connection that he yelled his battle cry, ‘workers of the world! unite.... you have nothing to lose but chains.’ Metaphorically speaking, these chains he referred to were nothing but the shackles of fear. With apologies to my revision of Karl Marx, one way of looking at things could be: “history of all hitherto existing society is the history of fear maneuvers....the fearsome have always exploited the fearful; but the point however is to change it for pan-fearlessness.”

Subba: A new formation of history itself, based on a fearism perspective and philosophy. I am writing about Marx and dephilosophy soon to be published.

Fisher: I so agree that the fearsome (elites, for e.g., and/or street gangs and other leaders) of history have tended to run the course of a logic of moral order upon the basic principle (written or not) that: Right is Might! However, that will not sustain sane or healthy existence in societies. Why? Because the “might” is part of the mechanism of terror(ism)/fear(ism) in its most toxic forms. I have, like Kumar suggested, thought that history (the human condition) is one of repeated (traumatic) Fear Wars. By definition: someone somewhere is out to see how they can make (force) someone else to become more afraid than themselves—and, that, supposedly (for the short run) produces superiority, power-over, domination, and rule. These Fear Wars are killing us all and destroying the planetary ecology that sustains life. We need alternatives, time is running short re: our cascading multiple crises. We need to critique everything we do as to when excessive fear is being induced for control in one form or another to dominate. This gets critical for police officers and military. A big topic. Suffice it to say, a new kind of education is required, and fear and its management has to be part of it. That’s why I am so delighted to have Maria as part of this dialogue. I am also heartened by recent teaching at the UN bringing fearism to police and peace keepers across several countries [9]. And so, I suggest, armed and unarmed, rich and poor, black and white, secular or religious, all can, if they allow it, get caught up in this addiction to fear-power-might. The game of control and who can give freedom and who can take it away. This patterned dynamic is so dangerous when it motivates “righteousness” (i.e., rules and laws) which motivates reactions and even revolutions.

Subba: As much as I see Kumar’s point of the complexity and situation variances. I still believe for poor and workers, their life is one of more satisfactory when it comes to fear. They have big hope of having daily food and finding a place to sleep. Street sleeper, beggar life is far better than rich in sense of fear. This picture we can see everywhere. It does not mean that I fully support we all live a life-style like of those persons; I support them, their space of hope. They have many spaces of hope. In comparing to their life, the rich person’s scope of hope is limited. Size of fear is less in poor whereas full fear is in the life of renowned person. When they have more fear, certainly they have more fear-related anxiety, depression, mental sickness, stress etc. Thank you for giving me chance to put my view. I think our dialogue will be fruitful to interested readers.

Kumar: Michael’s concerns are genuine in the sense that the so called authoritative ‘righteousness’ in the guise of laws and rules may foster the deadly combination of fear-power-might. After all, crime is a product of law, rule, regulation or procedure. As long as law does not talk about pass-port or visa, everyone used to roam freely across the international borders in the past. Now the pass-port Acts, visa rules, deportation and extradition procedures, etc. restrict individuals’ freedoms and define ‘non-adherence’ or any violation as crime. And then enters the police and other enforcement agencies, as the strong arm of the government to prevent/detect or investigate crime and to enforce law.

It is not illogical to say that people get such police that they deserve. If people are violent, police also have to resort to more of their coercive powers. The more intense the enforcement, the more fearful or aggressive the people are. If people are law-abiding, police rarely have to intrude into people’s privacy or conduct investigations as peace prevails in the society. When necessitated, police are required to use force as little as sufficient enough to bring back normalcy.

When laws were not enacted, there were also problems such as the reign of brutality of anarchy and fearsome chaos, the prevalence of unwritten practice of ‘might is right’ - whoever is strong, they arbitrarily dictate, etc. That kind of disorderly situation in the Babylon of 18th century BC forced King Hammurabi to formulate a code of conduct or laws that set the standards of orderly behaviour and justice. By this enactment, the hitherto prevailing unbridled freedoms of the mighty that led to fear, disorder and violence were regulated so as to facilitate order, peace and fearless interpersonal harmony.

Fisher: Maria, it is good to be reminded of some of this history of law. In future dialogues, however, I want to critically examine any so-called “fearless interpersonal harmony” as idea(l) under law, and what the actual real(ity) may have been.

Kumar: Subsequent civilisations also went on regulating the conduct of subjects/citizens through formal laws. Then what happens if regulations, enforcement and controls become more intense? Too much of regulation through laws and rules proves to be more harmful than helpful. If any aspect of human behaviour is controlled by unlimited creation and application of rules in the name of crime prevention, safety or maintenance of peace and order, what will happen to society as a whole? Same situation as aptly assessed by Michael will occur in terms of reactions and revolutions as history witnessed exactly 36 centuries after Hammurabi’s code that the 18th century AD’s French Revolution took place when the dictatorial monarch imposed too many of laws, rules etc. in the name of “liberty” while collecting too much tax, curtailing basic freedoms and denying food to people.

Lastly, as Michael said, we are inclined to design governance, create laws, make rules, regulations, policies and practices of enforcing them. I too feel that it is here in this context that a balanced approach is required to be devised so as to ensure that the governance intervenes least in the affairs of people except in the matters of life, liberty, equality, justice and the like; facilitates an environment free from fear and inconvenience while safeguarding the rights and interests of people and at the same time preserves and enlarges the freedoms of all individuals through appropriate moral and legal framework.

Fisher: Okay, lots to think about, for our next dialogue. Thank you both for a stimulating start on issues of fearcriminalysis. It has all got me thinking about at some point there may have to be a distinction drawn with a sub-field also related I’m coining fearpoliticology as more general than fearcriminalysis.

Notes:

- I have made slight modifications in uses of correspondence (as personal communications, Jan. 31- Feb. 1, 2018) for clarity, accuracy, English language use, and prompting purposes; but have attempted not to change the content and intent of the messages from my dialogue partners here.

- See, for e.g., Ulrich Beck’s work. Beck, U. (2003). An interview [by J. Yates] with Ulrich Beck on fear and risk society. The Hedgehog Review: Critical Reflections on Contemporary Culture, 5, 96- Also, Beck, U. (1999). World risk society. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press. Also Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. [Trans. Mark Ritter]. London, UK: Sage. This concept “risk society” overlaps with “culture of fear” (e.g., see Frank Furedi, Barry Glassner).

- De Becker, G. (1997). The gift of fear: Survival signals that protect us from violence. NY: Bantam Doubleday Dell.

- This is where I introduce ‘fear’ (with ‘ marks) to distinguish the topic and phenomena (i.e., fear) that I see dominating today in most societies, a morphing culturally modified ‘fear’—especially in the West where I live, in a culture of fear (e.g., see Fisher, 2010). Fisher, R. M. (2010). The world’s fearlessness teachings: A critical integral approach to fear management/education. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

- See Subba (2014), p. 322-23.

- Subba, D. (2014). Philosophy of fearism: Life is conducted, directed and controlled by the fear. Australia: Xlibris.

- Fisher, R. M., & Subba, D. (2016). Philosophy of fearism: A first East-West dialogue. Australia: Xlibris, pp. 57, 89. In part, Subba’s views have been validated in a recent research study and article, where Subba (2014) is cited in supporting evidence. See Farzana, S. U., & Mannan, A. V. (2017). Vernacular settlement vs. fractal geometry: A comparative study addressing popular density and space quality in rural Bangladesh. AIUB: Journal of Science & Engineering, 16(3), 1-8.

- Glassner, B. (1999). The culture of fear: Why Americans are afraid of the wrong things. NY: Basic Books. See also Glassner, B. (2007). The Gospel of Food: Why we should stop worrying and enjoy what we eat. NY: HarperPerennial.

- Specifically, I am referring to the workshop on fear management and fearism by a colleague of Desh Subba’s, his name is Furgeli Sherpa from Nepal, currently working with the UN Peace Keeping services as a police officer himself in Sudan; go to https://fearlessnessmovement.ning.com/blog/fearism-in-united-nation-workshop-room-mukjar-sudan

****

B. Maria Kumar (b.mariakumar@gmail.com)

Born on 5th April 1958, B. Maria Kumar studied biology at pre-graduation level, chemistry in graduation and business management and philosophy in post-graduation at Vijayawada, Guntur and Hyderabad (India) respectively. Joined Indian Police Service in 1985, he served in central India holding various positions in law enforcement and is presently working as Director General at Bhopal. Interested in literature, he wrote in his mother tongue Telugu and also in English. Some of his published titles are:

Mahimalesa Satakam (Telugu), Sanjivayya Satakam (Telugu), Vannela Dorasni (Telugu), Nenu (Telugu), Anandangaa Vundaalante (Telugu), Generation Z (Telugu), Voh Venus aur mein (Hindi translation), Poems d’Romance (Telugu), To Be Or Not to Be Happy (English), The Teapot Book of Love and Romantic Poems (English), Policing by Common Sense (English), Application of Psychological Principles in Maintenance of Law and Order (English), Be Selfish But Good (English), Kuch kadam aur khushi ki oar (Hindi translation), Psi Phenomenon of Nestorism (English)

Some works were translated into Russian language. Besides, he wrote articles in journals of national and international repute. Reviews of his works appeared in various newspapers. The following titles of honour were bestowed on him as a mark of recognition for his contribution to literature: Sahitya Sree, Vidya Vachaspati, Acharya, Bharat Bhasha Bhushan. He was also decorated with the following medals by the President of India in recognition of his services to police profession. Indian Police Medal, President’s Police Medal. Other distinctions won are: Singhast Medal ( Government of the state of Madhya Pradesh), EOD Medal (US Administration). He currently lives in Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India with his wife Vijayalakshmi. He has one son and one daughter.

Link to books available online:

https://www.amazon.in/Books-B-Maria-Kumar/s?ie=UTF8&page=1&rh=n%3A976389031%2Cp_27%3AB.%20Maria%20Kumar

Desh Subba (fearism@gmail.com)

Is a philosopher, poet, writer, and founder of the Fearism Study Center (Nepal) and leading expert on the philosophy of fearism.

http://fearism.blogspot.hk/

Pseudonym: Desh Subba, Full Name: Limbu Desh Bahadur, Address: 215, Yuk Ping House, Long Ping Estate, Yuen Long, New Territories, Hong Kong.

Date of Birth: 06 Dec, 1965, Birth Place; Dharan, Sunsari, Nepal, Fathers' Name: Kubir Jung Limbu, Mother's Name: Tilmati Limbu

Education: Master in business administration, Writing field: Philosophy of Fearism, Novels and Poems, Published Novel Books: Four novels, Doshi Karm 2050 B.S, Apman 2052 B.S., Sahid 2056 B.S., Aadibashi 2064 B.S., Philosophical Books: Philosophy of Fearism 2014 (English and Nepalese), It is translating in Hindi, Assamis and Burmese, Philosophy of Fearism- a First East-West dialogue 2016- English (co-author with Dr. R. Michael Fisher), Tribesmen's Journey to Fearless (Novel based on Fearism)

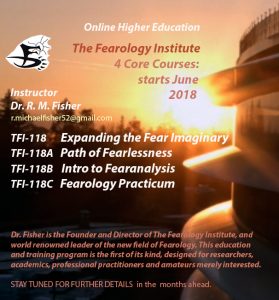

R. Michael Fisher (r.michaelfisher52@gmail.com)

Has a Ph.D. in Curriculum and Instruction (UBC), and is an educational consultant, editor, lecturer, independent scholar, writer and founder of the In Search of Fearlessness Project (1989-), In Search of Fearlessness Research Institute (1991-), the Center for Spiritual Inquiry and Integral Education (2009-), The Fearology Institute (2018). He is a world-renowned expert on the topics of fear and fearlessness and has published hundreds of articles and books on the topic and on education: The World's Fearlessness Teachings, The Philosophy of Fearism: A First East-West Dialogue (with Desh Subba), and Fearless Engagement of Four Arrows: The True Story of an Indigenous-based Social Transformer. His latest blogs are at the Fearlessness Movement ning which he began with his with Barbara Bickel in 2015. Also go to http://www.loveandfearsolutions.com